Ventricular Septal Defect

Introduction

A ventricular septal defect is a type of congenital heart defect where a baby is born with a small hole in the wall that separates the two lower chambers (ventricles) of the heart. Think of the heart as a house with four rooms - two upper ones (atria) and two lower ones (ventricles). Usually, both the downstairs rooms should have a solid wall separating them in between but in some babies, there’s a small opening or ‘window’ in that wall.

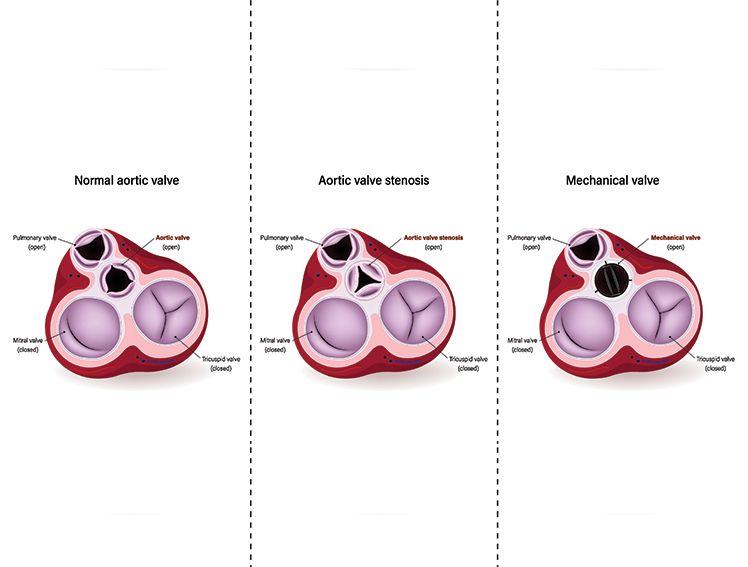

The heart functions as a pump with two sides. The left side pumps oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body, whereas the right side pumps oxygen-poor blood to the lungs to absorb oxygen. When there’s a hole between the lower chambers, oxygen-rich blood leaks from the left ventricle into the right ventricle. This extra blood flow makes the right side of the heart work harder than usual. Over time, it can put pressure on the lungs and lead to breathing difficulties.

What is Ventricular Septal Defect?

A ventricular septal defect occurs when the septum (a wall) dividing the two lower chambers of a baby’s heart does not fully develop before birth. This creates an opening through which there ought to be a thick wall. The magnitude of this opening is the determinant of the impact made on your child.

If the hole is small - as small as a pinhole- your child may not have many symptoms or any at all. A large number of children born with small VSDs lead an entirely normal life. This is not the case, however, when the opening is larger. The additional blood circulation leads to the overworking of the right side of the heart, which may cause it to be enlarged. The excess blood may also be directed to the lungs, and your child may be out of breath, particularly when feeding or playing.

The positive thing is that most small holes in the septum between the ventricles do close up by themselves as your child ages, the first three years in most cases.

Causes of ventricular septal defect

The precise causes of ventricular septal defects (VSDs) are often unknown, which helps reassure that these heart conditions are usually not related to anything parents did before or during pregnancy. VSDs generally form in the very early stages of fetal development when the baby’s heart is being built—often before the pregnancy is confirmed.

Genetic factors can contribute, especially when there is a family history of congenital heart defects. In such cases, healthcare providers may suggest genetic counselling and enhanced prenatal monitoring for future pregnancies.

While most VSDs are present at birth, a VSD can rarely develop later in adulthood, typically following a heart attack. These acquired VSDs are uncommon and different from congenital ones.

Overall, the development of VSDs is complex and not fully understood. Importantly, their occurrence is generally not caused by parental actions, which can help ease feelings of guilt among families.

Symptoms

Recognising the signs of a ventricular septal defect (VSD) helps caregivers know when to seek medical advice. Most symptoms become apparent within the first few weeks after birth, although they may be mild and easy to miss.

Common symptoms include:

Breathing difficulties: The infant may breathe faster than usual or show signs of struggling to breathe, especially during feeding.

Feeding challenges: The baby may tire quickly while feeding, take longer to finish a bottle, or appear too fatigued to feed effectively.

Slow weight gain: Weight gain may be slower due to difficulty swallowing and the extra effort the heart must exert.

Increased tiredness: Compared to other infants of the same age, the baby may seem unusually fatigued or less active.

Heart murmur: A healthcare provider may detect an abnormal sound when listening to the baby's heart with a stethoscope.

It is important to note that infants with small VSDs might not show any symptoms, or signs may develop later in life. Some individuals only discover they have a small VSD during a routine heart examination in adulthood.

Diagnosis

Ventricular Spetal Defect are usually indetified after the baby is born mostly when examining infants as part of a normal check. VSDs are so small that they are not generally visible on an ultrasound carried out during pregnancy unlike with some other heart complications.

Diagnosis normally takes the form of:

Physical exam: Your doctor uses a stethoscope to listen to the heartbeat of your baby, and he may detect a heart murmur, which is an additional heartbeat that denotes blood is passing through the hole

Echocardiogram: It refers to heart ultrasound. It is absolutely painless and enables the physicians to view the structure of the heart and observe the blood in real-time.

Further tests: Your doctor may advise additional tests, such as an ECG or chest X-ray, based on the size and impact of the VSD.

A heart murmur in children is often harmless, commonly referred to as an innocent murmur. When detected, an echocardiogram can help determine whether the murmur is related to a ventricular septal defect (VSD) or simply a normal variation in heart sounds during childhood.

Types of ventricular septal defects

Understanding the types of ventricular septal defects helps improve communication with healthcare professionals. Physicians categorise the VSDs according to the place in the heart wall where the hole can be found:

Muscular VSD: the most frequent is the muscular VSD, in which the hole occurs in the thick muscular portion of the wall between the ventricles. They tend to close together through the enlargement of the heart muscle.

Perimembranous VSD: It occurs in the membranous section of the wall close to the upper levels of the heart ports. They are the second most prevalent and might need constant checks on the child growing up.

Inlet VSD: This one is found around the place where blood comes into the lower chambers. They are less common and can be associated with other heart conditions.

Conoventricular VSD: This type is situated near the major arteries of the heart—the pulmonary artery and the aorta—and often requires surgical correction.

The position of your child's vsd enables the doctors to determine its chances of closing naturally and the nature of monitoring or treatment that may be required.

Complications from ventricular septal defect

If the hole in the septum is not too big, the symptoms may be insignificant. There may not be any severe complications.

However, if the defect is large, it can lead to a range of complications. Excessive pressure on the right ventricle can lead to heart failure. If the blood leaks into the lungs, it can lead to pulmonary hypertension and cause permanent damage to the lungs. Another complication of ventricular septal defect is the chance of a bacterial infection along the walls of the heart. This is known as endocarditis and is not very common.

Treatment

Sometimes in babies, if the ventricular septal defect is small, it may close on its own with time. If it doesn’t close on its own but also doesn’t have severe symptoms, you may not necessarily require treatment. Your doctor may monitor the defect regularly to check on the size of the defect and its symptoms.

Ventricular septal defect treatment depends on the extent of the damage, the age of the patient as well as the symptoms.

One of the symptoms of ventricular septal defect is that the baby or child grows tired while feeding. This could lead to malnourishment and the doctor may, therefore, prescribe a high-calorie formula. Some children are also prescribed medication that strengthens their heart muscles and lowers their blood pressure.

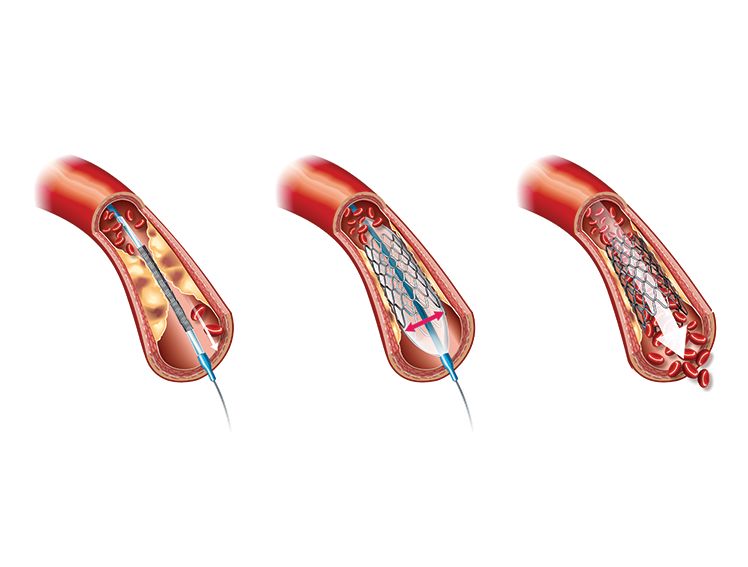

If the symptoms are severe among, ventricular septal defect treatment entails closing the opening in the septum. This can be done either using a catheter and placing a device to shut the wall or with an open heart surgery to repair the wall. While catheterisation is a minimally-invasive surgery, an open heart surgery is major procedure.

Following the treatment, your doctor will continue monitoring the situation with regular check-ups to see that the wall remains shut.

Conclusion

A diagnosis of ventricular septal defect (VSD) can initially feel challenging, but it is important to recognize that many children with small VSDs lead normal, active lives with minimal symptoms. Regular monitoring by a pediatric cardiologist is essential, and caregivers should seek medical advice if symptoms such as unusual fatigue, feeding difficulties, or breathing problems arise. The encouraging reality is that many VSDs close spontaneously without intervention, and when treatment is necessary, modern medical and surgical options are highly effective. With appropriate care and follow-up, most children with VSDs grow into healthy adults capable of engaging fully in everyday activities without significant limitations. Advances in pediatric cardiac care continually improve outcomes and support the potential for a healthy, active future.

References

https://healthcare.utah.edu/cardiovascular/conditions/ventricular-septal-defect

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17519398/

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/ventricular-septal-defect-vsd

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470330/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470330/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17684082/